Francine Falk-Allen

By Francine Falk-Allen

One of the first misconceptions that confronted me as a handicapped child was that people – children, adults, everyone – would often say, “I saw your picture on the March of Dimes poster!!” The March of Dimes was a campaign initiated to pay for polio vaccinations and patient care. Most of the patients were young children, who were the most prone to severe aspects of the disease. People were asked to send in “even a dime” and there were coin collection placards put out in stores, churches, gas stations, anywhere that people might be able to spare a dime. (A dime in 1950 would be worth about ninety cents in 2018.)

At first, when I heard that comment, I thought that somehow my picture was actually being used for the March of Dimes poster, and I was excited to learn this. I looked forward to seeing myself the next time I saw a placard around town. There I’d be, Francine Allen, the poster child. But I soon saw that it wasn’t my picture, though the girl was about my age, around five or six, wore a brace, used Kenny sticks (a half crutch with a canvas arm band), and had hair similar to mine, although hers was not in the meticulous ringlets my mother created to draw attention away from my limp. (If I looked pretty, it helped to make up for my defect, a concept I have never been able to drop.)

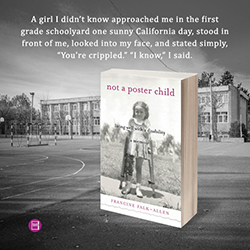

Falk-Allen is author of the book Not a Poster Child: Living Well with a Disability

I asked Mama if I was going to be the March of Dimes girl, and she assured me that I wasn’t, and that there were no posters out there with my picture on them. I was a little disappointed, but what bothered me more was that people didn’t recognize that it was not me, that any little girl with Kenny sticks and brown hair looked the same to them. It made me a little angry, that that was my identity: The March of Dimes Poster Girl.

It is possible of course that people thought, “What a brave little girl,” when they saw those posters, and that they thought the same of me. But I didn’t think of that when I was five-and-a-half. I was just perturbed that people could not see it was not me, and that I didn’t have a face to them, I had a limp to identify me. That’s one of my too early adult thought processes, required by the disease that took me away from home and into a hospital for six months when I’d barely just learned to run.

I was not a poster child. Not in reality and not in terms of the smiley, optimistic, never-bothered attitude that is often wished for in disabled people. Certainly that winsome courage is more appealing for the purpose of collecting donations! No, I was “head strong,” independent, ready with a smarty-pants retort, a girl who got out of a wheelchair and onto crutches before I was four years old, growing up a little too soon and missing some of the carefree aspects of childhood.

Later generations in the United States and Europe have not had to face these same issues, at least not with polio, and for this we can be thankful. Wouldn’t it be great if this deadly virus were eradicated once and for all, and all children could live without its specter? It is possible, and with the commitment of Rotary, we are moving toward that goal.

Francine Falk-Allen is author of Not a Poster Child: Living Well with a Disability – a Memoir, She Writes Press, 2018. She and her husband contribute annually to Rotary’s PolioPlus fund.

https://blog.rotary.org/2018/08/15/who-is-that-poster-girl/